First off, my apologies for going dark for a while there – between the holidays and a few other things, I was not able to keep up with the weekly schedule, ironically enough as I’m in the middle of writing about productivity. At any rate, we now resume our regularly scheduled posts.

Prioritization

At the core of being more productive is the skill of prioritization – deciding what is important and what is not, what to do first and what to do later, what to make as perfect as you can and what to make “good enough.” Prioritization is a concept easily explained and grasped, but much harder to put into practice day-to-day.

How Your Values and Goals Shape Priority

Prioritization literally means rank-ordering the things you want or need to do by importance. “Importance,” though, can be a slippery word. Important to whom, and why? Well, for personal productivity, “for whom” is necessarily for yourself, though obviously the wants and needs of others will factor into how important something is to you: as a father, your child’s needs are deeply important to you, as an employee your bosses needs may or may not be personally important to you, but for as long you want to keep that job, they’ll be practically important to you, and so forth. When it comes to importance that doesn’t come from anyone else, though, what do we do?

Luckily, our earlier work on getting clear on our values and goals gives us the answer. Work that gets you closer to your goals should be a higher priority than whatever doesn’t. Work that doesn’t align with your values should not be done at all. If you recall our discussion of strategy, you’ll remember that strategic thinking is all about linking bigger picture goals with lower-level means: if I do x and y here, today, then I’ll be more likely to do z there tomorrow. Obviously, there are various levels of “big picture” – what’s your plan for today, for the year, for your life, and the farther out you go, the less certain you can be about getting what you want.

Before we get to a handful of techniques to get you started on how to get more/better work done, let’s step through a few concepts that will help you to think more clearly about what to even do.

Important Against Urgent

The first idea derives from clarity on your goals, which help you to determine whether a given task is important or not. Important tasks are those that get you closer to one of your longer-view goals. If you have a goal of getting stronger and fitter by the end of the year, then your morning workout is important. If you want to get promoted at work, then giving the best presentation of your analysis you can is important. If you want to build a company, then developing your product or service, finding out who your customers are and what they value, and finding a way to get what you’re selling into their hands are all important tasks.

Some tasks, whether important or not, are urgent – if they’re to be done at all, they need to be done quickly. Responding to a minor question put to you by your boss might not be that important compared to the other work you’re doing, but if your boss expects prompt responses, it’s urgent. Getting packed for a trip the night before your flight is urgent, whether the trip itself or the packing are themselves important. You get the idea.

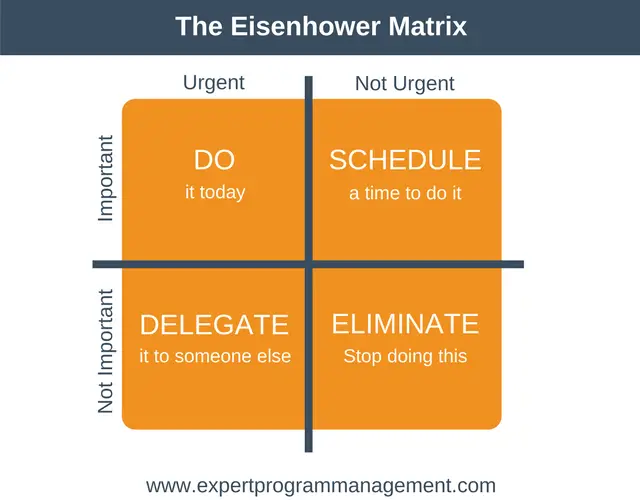

Being able to think of these two axes allows us to create a 2×2 matrix, that favorite tool of consultants, and, in fact, Dwight Eisenhower did exactly that.

Source: https://expertprogrammanagement.com/2017/07/the-eisenhower-matrix/

As you can see, the way these two qualities intersect can help guide us in how to take care of a task. Things that are both important and urgent, you should do yourself, right away. Things that are urgent, but unimportant, you should delegate (if possible, and if not possible right now, try to find a way to make delegation possible down the road, if it’s an repeated thing). Those that are important, but not urgent, since they’re easy to put off indefinitely, should get scheduled (and then you should respect that scheduling). Lastly, things that are neither important nor urgent should just not be done, they’re a waste of time.

This all sounds pretty simple when laid out explicitly like this, and it is, but we’ve all experienced getting sucked into low-value work, scrambling to play whack-a-mole with urgent tasks, and otherwise not following the advice of this model, so it’s helpful to have it as an explicit tool in our toolbox. Another nuance that makes practicing what we preach here difficult is that sometimes our obligations mean that the importance of a task to us is not the same as its importance to people you are obliged to. For example, imagine that you have started building a business on the side, but right now you need to keep your day job to pay the rent. What you need to do to make your side-business thrive is very important to you, but not to your boss. The work your boss asks you to do for your day job is somewhat important to you, since right now keeping your job is important to you, but it’s likely more important to your boss. Ideally, we want to shape our lives to a place where we eliminate these contradictions, but most of us aren’t there yet, and it may be impossible to fully harmonize all of the goals, values, and obligations of a complex life.

Dependence, Prerequisites, and Optionality

Sometimes the importance of a task is not inherent to it, but is instead due to the effect it has on some other task. If you’re going to build a machine, you first have to design it. Having a nice schematic is less important than the machine itself, but if it requires fine engineering, you likely need to get that schematic down on paper first, or else the machine will never get built. Another example is the travel mentioned above: putting clothes in a suitcase is less important than getting on the plane to go where you’re going, which is itself less important than the meeting that is the reason for the trip, but you can’t take the meeting if you don’t fly, and you won’t arrive with everything you need if you don’t pack, so these less important tasks take on a higher priority than they might otherwise “objectively” weighing their value. It can be helpful to have labels for these factors, going in both directions, so we can call those tasks that need to be achieved to make other tasks possible “prerequisites,” and those tasks that can be tackled afterwards can be called “dependent” on those prerequisites.

As you are thinking about prerequisites and dependencies can be a good time to consider a concept that receives a lot of attention in the world of finance, but has useful applications outside of it: optionality. If completing a task would give you more options than you have now, it has “optionality.” So, going to school and getting a degree that’s required for certain jobs gives you more optionality. You can still take all the jobs that don’t require it, but now you can also apply to the jobs that do. A med school grad can become a doctor or a plumber, whereas a high school grad only has the latter option available (if those are the only two jobs, of course).

Generally speaking, optionality is desirable. If you have more options, the likelihood that one will be better than the others is higher, and so you’re more likely to have a good choice available. This is one of the many reasons most of us would rather make more money than less: money is almost pure optionality. Anything you can buy, more money makes it more likely that you can buy it. The reason I’ve brought this up while thinking about dependence and prerequisites is that when you’re thinking strategically, very often, all other things being equal, the better move to make is the one that gives you more optionality. To continue the education example, getting an undergraduate degree is a prerequisite for many things further down the line: medical school, law school, an MBA, a Masters, and so forth. Since an undergraduate degree is a prerequisite for so many things, it confers a lot of optionality, which is one of the many reasons they have been so sought after by so many people, at an accelerating rate, for the past several decades, at least (notice also that the number of jobs and forms of training that have made an undergraduate degree a prerequisite has increased, further expanding the optionality, and thus the perceived value of a degree).

Pursuing optionality, then, is a good heuristic, an approach that is very often at least mostly helpful. But it can be taken too far. Often, folks who strive for optionality do so to avoid choosing a goal further down the line. Someone who goes to undergrad to create options, then takes a job with a consulting firm to create more options, then goes to a prestigious firm because having it on his resume will give more options, and so forth, might coast through 5, 10, or more years of his life without knowing where he really wants to end up, and by the time he figures it out, he may be in a worse place than if he had followed a less-option-rich path, but one that was more direct. All of which is to say, I encourage you to balance the usefulness of optionality with as clear an understanding as you can get with your longer-term goals, which is why we went through the effort of thinking through values and the goals that align with them first.

The Value of Elimination

So far, we’ve mostly focused on choosing what to do, but when it comes to getting the things that matter done, it is often even more useful to think through what not to do. Unless you retire to a monastery or mountain hermitage, there are likely to be a near infinite set of things you could do, and many of those things will be presented as requests, entreaties, or demands from others. Who do you say no to? Who do you help? Even by yourself, though, this can be a challenge. If you like to read as much as I do, no doubt there are entire shelves of books in your room or in the library that you want to read, but which one do you pick up today? When I was in college, I realized there were several things I liked to do that I was doing less of than I might wish: reading, drawing, spending time with friends. So, I looked at how I spent my time and realized that one of the things I enjoyed was playing video games, and doing so was reducing my time to do the other things I liked. So, I made a rule that except for a few special exceptions (like Zelda and Metroid games), I would only play video games with my friends. It wasn’t that I thought I was playing them “too much,” nor that there was anything wrong with them, it was just that I valued reading and drawing and socializing more.

So, on the more practical side, it is helpful to look at our personal and professional lives and ask which parts are less valuable, less aligned with our values, or less helpful in reaching our goals, and then to see what we can to do to minimize or eliminate those things. One of my favorite writers, John Michael Greer, is a big advocate of getting rid of your television as a way to reclaim several hours of your day, if you’re anywhere near the average in TV viewing. Tim Ferriss’s The Four Hour Workweek is largely concerned with ways to cut down on doing the less-important stuff so that you can focus on the more important.

Once again, what is important (or not) for you will depend upon your goals and values, and might look very different for me. Maybe football is vitally important to you, and watching the game with friends and loved ones is a central ritual for you – okay, so you likely don’t want to get rid of your TV, then, but if prestige dramas are less important to you, maybe it becomes a football-watching device only. You’ll have to figure it out for yourself, but that’s the kind of thing high-agency Renaissance Men learn to be good at.

A Reminder on Satisficing Against Maximizing

We briefly touched on satisficing vs maximizing in an earlier post on strategy, but I wanted to bring it up in the context of productivity, because it can be very useful to consider when prioritizing what to do (or, as highlighted in the previous section, what not to do), as well as how much effort to put into something. If you have clearly identified a task as better suited to satisficing (it produces diminishing returns after reaching a certain point), but still important, then you want to do it until you reach the point of diminishing returns, and then stop. On the other hand, things that are worth maximizing (they have linear or exponential returns, the more work you put in, the better the result) are far more likely to be important, and thus to be prioritized and given as much effort as you can afford to give them.

A Handful of Techniques

Okay, with all of that groundwork laid, we can now get into a bit of the kind of stuff you’ll find if you read books on “productivity” as its own discipline. As I mentioned last time, this field can be a very deep rabbit hole, if you find that interesting or helpful, so I don’t propose to give you anything like a comprehensive overview, still less the “end all, be all” of “how to get things done.” Instead, I’d like to share a few of the approaches to work that I have found consistently helpful, in some places, contrasting approaches so you see which ones work better for you, and a few reminders of fairly obvious things that are nonetheless easy to neglect in practice.

Build the foundation – Take Care of your Body

We’ll start with one of those seemingly obvious things that we all know better, and yet many of us fail to follow our own advice: taking care of your body. Sure, sometimes we can push through lack of sleep, not enough food, and being physically inactive to get something done, but as a baseline, it’s a bad approach. One of the core issues in being productive is being motivated enough to do what you say you want to do. We’ve all been in situations where we had a task we know needs to get done, that is actually personally important to us, and may not even be all that hard, and yet, we don’t do it. Why? Because we’re not motivated enough. As we discussed while covering the Will, we can train ourselves to be less dependent on motivation, but to be fair, everything is easier when you have it.

It turns out that a good deal of what makes up motivation is plain, old physical energy. If you are well-rested, well-fed, and your body’s in good shape, you have a lot more motivation than when you’re tired, hungry, or weak. Again, sounds pretty obvious when I put it that simply, but it’s all too easy to get out of the habits that make the former our default state.

Perhaps even more than the other material below, this section is really one where one size doesn’t fit all. Different bodies respond in different ways to the same diet, the level and kind of exercise you need to feel fit and healthy may be far more than for me, and some people just need more sleep than others. So, listen to your body. If you feel gross and sluggish after a meal, maybe try something else next time. If you try out some miracle diet, see how you feel. For example, I had read all of these glowing reports of people on the ketogenic diet about how much energy they had, how sharp cognitively they felt, and how much less sleep they needed. Sounds great, sign me up! Well, I followed the diet strictly for several months, checking my blood ketone levels to make sure I stayed in ketosis, and you know what I found? I felt slightly less tired when I didn’t get enough sleep, I had a bit less mental “fog” when I was hungry or tired, and being hungry between meals bothered me less, so I didn’t feel much need to snack. Sure, I lost the weight that had been my main reason for giving it a try, but my blood pressure was a little high, and I didn’t feel like the superhero some advocates said they did, so I decided it wasn’t for me. Even worse, a few months later, I tried it again, this time trying to get most of my fat from plants (think big salad doused in olive oil), and this time, I felt terrible. I was groggy and listless almost all the time.

Point being, different diets, different workout routines, different sleep schedules work better or worse for different folks. So, experiment, pay attention to how you feel, and try to find a set of practices that you can do consistently, even if they might not be as intense as you hoped. The 10 minute calisthenics workout you do every day is better than going to the gym for 3 hours for a week and then giving it up. The diet that’s pretty healthy, but you stick to, is better than the one you follow for a few months and then go back to eating unhealthy foods because you miss them too much. You get the idea.

Tracking What You Do: To Do Lists

One of the oldest and simplest productivity tools is the humble “to do list.” I know you already know what it is, but for the sake of completeness, it’s where you write down the various tasks you need to get done somewhere that you’ll see it (on your phone, on a sticky note, in your notebook, etc), and as you get those things done, you check them off or cross them out. The reason these are so widely used is because they are simple, effective, can easily be scaled up or down in sophistication, and help to deal with the problem of forgetting to do something because some other task pushed it out of your mind.

Personally, I find to do lists most useful for relatively mundane tasks that nevertheless need to get done, especially when they are part of a sequence for achieving a bigger picture task (like a grocery list). The potential downsides I’ve found with to do lists are that they tend to grow as you use them, things go on the list, but then never get done because you keep prioritizing something else, and eventually this starts to feel constraining. You’ve got this list of things to feel guilty about not doing, and it just keeps getting bigger. Another potential downside is when folks attempt to upgrade simple to do lists into elaborate systems (I got pretty carried away there for a while back when I was a consultant. My tasks had weightings for priority, points to reflect how much effort they’d take, categories, etc. It was nuts). Usually the elaboration comes as some way of trying to get the to do list to do more than just keep track of “done/not done.” Folks start re-arranging by priority, having a way to carry tasks over from one day to the next, integrating it with their calendar to schedule when to do things, and so forth. Sure, some of those “features” might be helpful (and, to hammer on the same theme, might be helpful for you, even if not for me), but there’s a risk of adopting a complex approach while enthusiasm is high, and then abandoning it when it wanes, which usually results in dropping all of it, instead of just the additions that made it too cumbersome.

Tracking How You Spend Your Time

An alternative to tracking the tasks you have to get done is to track the time you spend working. The idea here is you don’t write down the dozen things you might do for your small business today, but instead plan on spending two hours doing whatever needs doing. Obviously, you can combine these: you go to your shared work space to spend two hours working, and on the whiteboard is your ongoing list of things that need to be done. I like to separate them, though, because to me, they “feel” very different. To do lists focus on the outcome, whereas time tracking focuses on the process. There are pros and cons to both emphases, and I think some people find one or the other more congenial.

One way to track time is called “Time Blocking,” which I learned from Cal Newport. He encourages people to take out a notebook, along the left hand line define the hours of the day, and then make a plan for the day where every hour part of a “block” of time where you’re focusing on something. So, in the morning, you might have two hours of “start up time,” then an hour of “check and respond to email,” then 30 minutes for a coffee break, then 1.5 hours of “research,” and so forth. You can be as specific or as broad as you find helpful – maybe instead of “start up,” you put “product development,” or “sales outreach.” One key point that Newport stresses is that the goal is not to follow your initial plan, no matter what. The goal is to have an idea of how your day is going to go, but as things come up, to change it as needed, but when you make the change, to still have a plan, it’s just a new plan. You start checking your email around 10:00, find an invitation to meet with that investor you’ve been trying to get in touch with this afternoon, and now you need to head home, change, and drive to the place he wants to meet. No problem (great, even!), just block out the rest of your day with your new plan a little to the right of your original plan. As for downsides, for me, having every minute of my day “spoken for” can feel constraining, regimented. Sure, sure, you can put a four block that says “do whatever I want,” but part of the point of this approach is that it subtly nudges you to not do that, to focus on what matters and try to do as much of it as possible. At least, that’s how it makes me feel, but I do sometimes find this helpful, especially in very busy periods with lots of moving parts I have to remember to give at least some attention to.

An even simpler form of time tracking is called “The Pomodoro Technique.” It is so called because it makes use of a kitchen timer, and the guy who came up with it was Italian, in Italy kitchen timers are often shaped like tomatoes, and Pomodoro is Italian for “tomato.” Anyhow, the idea is that when you have some task you know you need to spend time on and you don’t want to get distracted, you set the timer for 20 minutes, and for those 20 minutes, you focus on the work (the creator was a grad student who was making himself do the research and writing he needed to do for his dissertation). When the timer goes off, give yourself a 10-minute break, and if you still have work to do when you come back, set the timer again. This technique does less to help you decide what to do or when to do it, but rather helps to reinforce whether you actually do it as intended. That makes it an excellent support for what we’re going to talk about next, which is focus.

Deep Work Beats Shallow Work

In his book Deep Work, Cal Newport lays out the value of what he calls “deep work,” especially compared to the far more common “shallow” work. One part of deep work is what we’ve talked about above when we discussed values, strategy, and prioritization: working on things that truly matter. The more tactical consideration, assuming you’re working on things that matter, is to focus. By focus, I simply mean the ability to do one thing without distraction for a decent amount of time. Simple, but not so easy, especially in the terminally distracted world we live in. Push notifications, pop-up alerts, text messages, calls, TVs in every corner, endless scrolling videos right in your pocket – it’s easier than ever to fall prey to distraction, but the good news is that with some effort, we can reclaim our ability to focus. Focusing is very much like a muscle – when you exercise it, it gets stronger, and when you neglect it, it gets weaker. So, if it’s been a while since you flexed this muscle, it’s alright to start small – that’s exactly what the Pomodoro technique was invented to do! Just 20 minutes of working on what you have identified as important, and then a break to do whatever you want. When you’re starting out, that first block is all you need. Over time, though, you likely want to get “stronger,” just like you would in the gym. One way to keep track of this is to log how many blocks you manage in a day. Just so you know, somewhere around 4 hours of truly focused, un-distracted work seems to be the upper limit for anything sustainable. Sometimes you might pull more if you get deep into a flow state, but that can’t be expected for day-to-day work. Getting to an hour, whether continuous or not (so, 3 pomodoro blocks, which would actually take you an hour and a half, including the breaks) is a good, reasonably ambitious target to shoot for within a few weeks.

But why do we want to focus? Focus is a super-power. If you have never cultivated focus, you might be surprised at how much work you get done in the same amount of time as more distracted folks. When I was a consultant, we had rather a lot of work to do, and my colleagues were quite productive. On the other hand, it was normal to keep working in the hotel after leaving the client, to spend entire flights working, and to otherwise “always be working.” Once I made focus a priority, I didn’t have to engage in these behaviors. When I left the client, I was through for the day. I spent my (frequent) flights reading books. I even had wiggle room to work on side projects. All because when I was working on client work, I focused on that and didn’t let myself be distracted.

Now, of course, there are some challenges, and as with anything, there are trade-offs involved. Since most people around you are not focused, they will feel free to jump in and distract you when you’re trying to focus. Setting the boundaries that will stop this from happening can ruffle some feathers and have some downsides. At the end of one project as a consultant, my manager was giving me feedback on how I had done. He praised the high quality and large volume of the work I had done, but then he said “it’d be nice if you were a little more present and interactive in the team room.” Luckily, we had a good relationship and he shared many of my views on the value of focus, so I was able to say to him “I understand that, but the lack of interaction is what lets me focus, which is how I produced so much good work.” He understood that, but said I ought to try to strike a balance anyway (as a manager, he necessarily has to balance the kind of distracting coordination “work” like meetings with the more focused production I was optimizing for).

There’s a few tips that can help with focus. First off, I find music very helpful, especially if listened to through noise-cancelling headphones. I have a “working” playlist (listening to it right now, actually) made up purely of the kind of music I find most useful for focused concentration (in my case, lots of synthwave, Daft Punk, and chiptunes music, largely instrumental), and I only listen to that playlist when doing focused work. That exclusivity makes the music a subconscious cue that it’s “focus time.”

Another tip is one that I learned from Mary Stearn’s book The House that Cleans Itself, which as the title suggests, is all about housekeeping, which might sound a bit strange in this context, but one of her key concepts is actually transferrable to all kinds of domains in life: if you want to do the right thing more often, make it easier to do the right thing. An example from her book: if you find trash not ending up in the trash can, get more trashcans. One per room, or even more. Often these kinds of interventions sound dumb or unnecessary: “come on, it can’t actually be too hard for me to walk to the next room to throw stuff away, I’ll just be better, try harder.” But when you observe your behavior, if you’re not getting the outcomes you want, consider making a change to make it easier. When it comes to focused work, this means things like turning off as many push notifications as you can get away with, deleting go-to distracting apps, giving yourself cues (like a playlist, a particular place to work, or what have you), or installing apps that limit your time on the internet. I know one author whom I respect very much and has an incredibly voluminous output (John Michael Greer) who goes so far as to have a writing laptop and an internet laptop. The writing laptop never connects to the internet and only hold files relevant to writing projects. That approach might be a bit extreme for most of us, but it certainly works for him!

Lastly, if you really want to level up your ability to focus, consider taking up meditation. Meditation is to focus what lifting weights is to physical strength: the pure, irreducible practice of strengthening what you’re trying to strengthen. I won’t go into a detailed description here (maybe another time), but there are many kinds of meditation, and the “mindfulness” meditation most commonly taught these days might not be the best fit for you (it wasn’t for me). The form of meditation I’ve had the most success with is called “discursive meditation,” and it has a long history here in the West. It was commonly practiced by ordinary people right up until the early 20th century, when it began to fall out of fashion, leaving a gap in the mental and spiritual practices of Westerners that has been partially filled by Eastern practices since the 1960s or so. In discursive meditation, the goal is not to turn your conscious mind “off,” or to reduce it to paying attention only to your breath, but rather to harness it in an intentional, focused way. I find it incredibly helpful to explore deep philosophical and spiritual matters, and incidentally, I find it far more compelling (and thus easier to stick with) than mindfulness meditation, with many of the same benefits in calmness, focus, and mental clarity. If you’d like to give it a shot, the same John Michael Greer I mentioned before has an admirably straightforward set of step-by-step instructions that can be found here.

“Eat Your Vegetables Before Desert”

I got this piece of advice from Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s late business partner. The idea is to do the less-pleasant, but necessary, things before you do the things you’re excited about, using the prospect of doing the thing you want to do as motivation to get through the things you don’t want to do as much. Say there’s a book you’re reading for research that you are finding really compelling, but you need to make some progress on the book (or blog post…) you need to write. Set yourself a target for cranking out some writing, and then when you finish you get to read as a reward. Obviously, “dessert” doesn’t have to be work related: maybe your reward is to watch a funny video or read some fiction, but if you’re trying to be as “productive” as possible, you can select necessary, but more enjoyable things as the reward. One warning here, though: just as you don’t regularly want to have meals with a single carrot followed by a whole pie, you have to be clear-headed about the ratio of “vegetables” to “dessert.” Far too many times, I’ve said to myself “okay, I just need to knock out this little bit of work, but if I do, I’ll reward myself with reading a bit.” Then I work for maybe 20 minutes and “reward” myself by reading for a couple of hours. Not so bad if the reading is worthwhile, of course, but if I was rationalizing it as a way to get work done, the reward might have been disproportionate. So, if you’re like me, keep an eye out for that way of tricking yourself.

Building and Keeping Habits

Fundamentally, if we want to get more of the right things done consistently, we need to build habits that support that, so it might be helpful to briefly talk over a few key concepts around habit-building. As most of us have experienced, habits can be very powerful, for good or ill. We fall into unhelpful patterns that we just can’t seem to get unstuck from, but some of also effortlessly do things consistently that others struggle with, all because of the force of habit. Once established, habits allow us to do things more or less on autopilot, which, again, is great for the things we want to be doing, less great for those we don’t. So, how do we go about building a habit we want to have?

The first thing to know is that it’s good to start very small: pick the smallest possible increment of doing the habit and practice that until it sticks, and only then worry about doing more with it. For example, say you want to start a daily morning workout. Eventually, you might want this to be fairly involved: going to the gym, weights, running, the works. But if you try to go from no working out at all to spending hours at the gym, as many do come New Year’s resolutions, you’ll bounce off pretty quickly. Instead, pick something so small you almost can’t skip it. A single push up. Five minutes of walking. Whatever it might be, the goal is that you will do it every single day, no matter what. Once you’ve got that under your belt and it feels automatic, you can start gradually creeping up (maybe 5 pushups, or 1 push up and 1 sit up). I like to say “consistency is more important than intensity,” because you have your whole life to accumulate the fruits of steady habits, but only if you establish them. I got another, even pithier way to think about it from Rune Soup: “it’s okay to suck, it’s not okay to skip.”

Another idea that helps with getting that consistency going is to focus on only building one habit at a time. Maybe you want to be healthier, so you think you need to change the way you eat, work out more, spend more time outside, get better sleep, and get more steps in. All laudable, worthwhile goals, to be sure! But if you wake up tomorrow and try to do all of these things, you might struggle. So, instead, pick one of these things, work on doing it consistently (starting small, as we said), and wait until it feels fairly automatic to move on to the next habit.

Speaking of multiple habits, it can also be helpful to “chain” related habits. Think of your morning routine, and you likely have an example of doing this. You wake up when your alarm goes off, a long-established habit, and without thinking you go and brush your teeth, because that just always comes after waking up, another long-established habit. Then it’s normal to get in the shower, then to comb your hair, then to get dressed, then to make coffee, and so forth. You can also take advantage of this more intentionally. Maybe you make your morning workout the thing that follows brushing your teeth, and then meditation naturally follows working out, and then a shower after that. If this is new, it will feel like breaking an established habit, but over time, the new rhythm will come to feel natural, and soon skipping the workout or meditation will feel just as weird as skipping brushing your teeth or taking a shower.

In a lot of writing about habits, the focus is almost entirely on the value and necessity of keeping habits, with little acknowledgement that we are, after all, fallible humans. I would feel like the worst hypocrite in the world if I didn’t admit that I’ve had more than my fair share of breaking desirable habits and staying stuck in undesirable ones. So, while it is powerful and desirable to build good habits, it’s also important to give yourself a bit of grace. We’re in it for the long haul. I meditated every day for three and a half years, went through a rough patch, got spotty about it, and now I’m working my way back into my former consistency. Stuff happens, and we’re not always going to be able to live the perfectly designed, entirely consistent lives we might wish. One tool you can use to minimize the impact of disruptions is “fallback habits.” These help us to live up to “it’s okay to suck, it’s not okay to skip.” Say your daily workout has progressed to something fairly elaborate, and usually it’s no big deal to spend 30 minutes or an hour working out, but today you’re sick, tired, and running late. Rather than abandoning the habit entirely for the day, consider doing something much smaller: go back to your single push up, or for meditation, just spend 30 seconds doing mindful breathing. This allows you to not “break the chain,” as Jerry Seinfeld would put it (he made it a habit to write at least one new joke every day, and once it was written, to put an ‘X’ on that day on the calendar, and the goal was to have an unbroken chain of Xs). Once again, this is a place where you have to know yourself: if you’ve spent a year doing your “fallback” habit everyday, maybe it’s not actually the fallback, maybe that’s all of that habit you can manage at this place in your life. Or maybe you’re not pushing yourself where you could. It can be hard to know, and getting the right balance of not being too hard on yourself with not cutting yourself too much slack is itself a skill and habit that takes a lifetime to master.

Use Checklists for Repeatable, Important Processes

In The Checklist Manifesto, surgeon Atul Gawande extols the many and great virtues of the humble checklist. Among others, through the simple introduction of a checklist to be used before surgery, thousands, if not millions, of lives have been saved by the reduction of accidental complications. Checklists are most valuable for tasks that you are going to do over-and-over again, and most especially for those where small, easy to overlook mistakes can have large negative consequences, but can be avoided with a simple reminder. To use an everyday example, think of a grocery list. Remembering to buy any one thing on the list is well within our power. But when you have a couple dozen things to buy, you’re navigating around clueless shoppers blocking the aisle with their carts, and you’re explaining the late republican Roman civil wars to your daughter, it’s all too easy to forget that one thing that was perfectly clear to you back home in your kitchen (and will be once again when you’re back and cooking).

Checklists work best for things that you do relatively frequently. One reason for this is that you get economies of scale for the work you put into crafting the checklist. It’s a better “return” to spend a week coming up with a checklist for something you do every day than something you do once a year. The other reason it’s more valuable is because no checklist is perfect as a first draft. The very nature of the kinds of tasks suited to checklists is that they’re made up of many, small sub-tasks that are easy to overlook, especially in the abstract. The way you fix this is to come up with a checklist, start using it, and then pay attention to what isn’t on the checklist that should be (the thing you see at the grocery store that you didn’t think of when making the list, but realize you actually do need) and to the things on the checklist that don’t need to be there. The flip side of this, of course, is that checklists might be overkill for things that aren’t repeated often enough, don’t have big enough consequences for getting wrong, or that are highly variable. In such cases, the work put into developing the checklist, and the effort that goes into following it, can come to feel like a burden. Right after reading Gawande’s book, I went checklist crazy, got a checklist app for my phone, and tried to make checklists for almost everything I did in a day. Eventually, it was just exhausting, and the benefits were too small to justify the effort. So, use checklists with care, acknowledging their value where relevant, but not trying to turn your entire life into a clockwork apparatus, with every moment a clearly defined step in a flowchart.

Delegation

Our last tip, which we’ll discuss in more detail when we get into leadership, is that one of the easiest ways to get more work done is to get some help: you might be able to delegate some of the things you’d like to see done. Obviously, there’s some work you can’t delegate meaningfully: if I pay you to work out for me, I’m not going to get any stronger! That’s an intentionally silly example, but the core concept important to keep in mind. Say you’re a writer, you find some success, and your publisher wants books faster than you can write them. At first glance, hiring a ghostwriter to do some of the writing, with your editorial oversight, might seem like a good way forward. But keep this up for too long and pretty soon folks won’t be reading your books, they’ll be reading your ghostwriter’s. So, beware of delegating away tasks that are a core part of your value proposition, especially those where the doing is itself the practice (writing is how you get better at writing, selling is how you get better at selling, and so forth).

That said, often there is work that can be usefully delegated, and sometimes in ways that not only free you up to do more of what it’s more important for you to do, but that actually make the delegated work better. To go back to our writer example, it might not make sense to delegate away the writing itself, but what if you found a talented research assistant who is actually better than you at research? Now, not only do you have more time to write, you’re also working with better quality research, and so hopefully your writing is even better. Obviously, delegation is more important if your goals require an organization to accomplish them. A writer is less likely to need to master delegation than the founder of a company building tools for makers.

As I said, we’ll come back to delegation when we’re talking about leadership, and we’ll spend more time there on when it makes sense to delegate, why delegation is essential in developing those who work for you, and the benefits to the task at hand of effective delegation. From the standpoint of getting things done, though, the key takeaway is that one way to get more of the important stuff done is to get someone else to do the less important stuff. Whether that means hiring an assistant, bringing in an intern, or hiring more employees, “many hands make the load lighter.” Now, an important clarification: I said “more” and “less” important tasks, but what I really meant was “less important for you to do them.” Tracking employee hours and pay is very important, but it might not matter whether you or someone else does it. You wouldn’t be delegating the work if it didn’t need to happen at all. Rather, you delegate work when the opportunity cost of doing it yourself is higher than the costs of having someone else do it (in purely monetary terms, if you can be doing things that bring in or save more money than it costs to hire someone to do it, then you should hire him).

So, if you find yourself struggling to do all that you would like to be doing, ask “is there a way I could get someone else to do some of this work?,” then start identifying which work he could do, and then go out and find him.

A Final Reminder: Productivity is a Means, Not an End

We’ve spent rather a lot more time on “productivity” than I originally intended. It’s a rabbit hole that you can fall very deeply down indeed, as I have in the past. I do believe that the tips, techniques, and concepts we’ve gone over can have value, and I hope that you find a few of them worthwhile in your own endeavors. But I’d like to remind you that all of these tools are means to make it more likely you achieve your goals, not ends in and of themselves. Logging 20 pomodoro blocks in a day is no accomplishment if the thing you were focusing on doesn’t matter. Crafting a perfect plan for the day and following it to the letter doesn’t help if that plan isn’t consistent with your values or doesn’t get you closer to your true goals. Getting to “Inbox Zero” is meaningless if you’re not corresponding with interesting and worthwhile people. You get the idea. Stay focused on your big-picture goals, as informed by your values, and use whether you’re getting closer to them or not to judge whether you need to be more “productive” or not.

Discover more from Rhetoric for the Renaissance Man

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.